|

Research over the past twenty years

has revealed Giuseppe Valentini (1681–1753) to be a figure of considerable importance in early-eighteenth-century Italian music.(1) As both a violinist and a composer (of operas, oratorios and cantatas, as well as instrumental pieces), he was evidently one of the most prominent musicians active in Rome from around 1700, achieving substantial success there with his sonatas and concertos even

before the death in 1713 of Arcangelo Corelli. Besides his several published collections issued in the period 1701–24, numerous instrumental works survive in manuscript, including nine preserved in Manchester (in a collection

described below), twelve in the archive of the Scuole Pie di S. Pantaleo, Rome, and six in Dresden.(2) Working often in a freelance capacity, Valentini received patronage in Rome from various churches and important persons, many of whom were connected with the Arcadian Academy. Most pertinent to the concerto

presented here is his association, notably in

the 1720s, with the court of Cardinal Pietro

Ottoboni (1667–1740).(3)

To the best of my knowledge, the only known source for the present work is a set of eight manuscript parts within a large collection of Italian music now known as ‘The Manchester Concerto Partbooks’.(4) Since the history and contents of this significant collection, representative of the heyday of the Italian concerto, are assessed in detail elsewhere, only a summary needs to be given here.(5) The volumes contain sets of separate parts for 95 compositions, mostly concertos, that came into the possession of Charles Jennens, well-known as the librettist for Handel’s Messiah and other works; later they passed to the music libraries of the earls of Aylesford and Sir Newman Flower. It was Jennens who had acquired the music from Italy and had it bound in its existing volumes. Earlier, in its unbound state, the collection had almost certainly been part of a much larger corpus: the music amassed over many years at Cardinal Ottoboni’s court, sold off after the illustrious patron’s death in 1740. The diverse contents of the concerto collection suggest that Ottoboni’s musicians acquired and performed music from artistic centres elsewhere (notably Venice and Bologna) as well as works composed locally.

Like most pieces contained in the partbooks, the source for the present work is a utilitarian manuscript intended to be used in performance rather than to grace a library shelf. Catalogued as item 28, it belongs to the largest

subset of the collection: 43 works copied on

Roman music-paper by scribes who are likely to have worked at Ottoboni’s court, in and around the mid-1720s.(6) The eight parts’ original

nomenclature and location within the partbooks are as follows:

First recorder

& oboe: Flauto, et obuč Primo

volume xiv, ff. 17–18

Second recorder

& oboe: Flauto, et Obuč 2.o

volume x, ff. 15–16

First violin of

the concertino: Violino Primo Concertino

volume i, ff. 58–61

Second violin of

the concertino: Violino 2.o Concertino

volume ii, ff. 42–45

Violoncello of

the concertino: Violoncello del concertino

volume vi, ff. 49–52

First violin of

the ripieno: Violino Primo di ripieno

volume iii, ff. 36–37

Second violin of

the ripieno: Violino 2.o di ripienov

volume iv, ff. 38–39

Basso of

the ripieno: Basso di ripieni

volume v, ff. 15–16

The wind parts are of special interest in that each calls for both “flauto” (here meaning the standard flauto dolce, an alto recorder) and “obuč” (oboe). This reflects the common practice of the time whereby woodwind players were expected to perform competently on more than one type of instrument, alternating between them as required. On rare occasions this would involve swapping one instrument for another even within the same piece, as the second movement of the present work demonstrates. Cues given in the manuscript (quoted in the Textual Notes, below) indicate the choice of instrument at every stage. If suitable personnel are available, the solution of engaging oboists who are capable also of playing the recorder parts naturally remains the best one today.

The Roman terminology (“del concertino”, “di ripieno”, etc.), which would typically indicate the concerto grosso disposition of an

ensemble, does not in this case reflect the reality of Valentini’s musical design. (This is a traditional nomenclature doubtless used by the Roman scribes out of habit.) Discounting minor errors, there is no textual distinction

between the concertino and ripieno string and bass parts, and indeed no solo passage to be found, except during the third movement. Consequently, for movements i, ii and iv in the present edition the various parts are combined as first violin, second violin and basso (including cello). In those movements continuo realization of the bass part is presumably intended, even though the violoncello del concertino and basso di ripieni parts contain no bass figurings or any other features to confirm that conclusion. In the case of the third movement, where the basso di ripieni part is silent throughout, we may be reasonably certain that the bass phrases appearing in the cello part (bars 1-8, 18-23 and 38-44) are not to be realized.

Only the part for the first recorder and oboe identifies the composer and gives a title for the work, having been designed as a folder into which the remaining parts could be inserted when not in use. The music itself begins on the second page (f. 17v), following a title-page which reads: ‘Flauto, et obuč Primo | Concerto Con V.V. [violini] obuč, e Flauti | Del Sig.RE Gioseppe Valentini | Fogli 5,4 ÷’. Those words, like most of the manuscript’s text, are in a notably competent, presumably professional, hand; the same copyist was responsible for several of the collection’s other compositions by Valentini (items 25, 51, 64 and 65). A second scribe was responsible for writing out the Violino 2.o di ripieno and Basso di ripieni parts. Since the manuscript employs three particular varieties of five-stave music-paper that appear elsewhere among the collection’s Roman manuscripts, there can be little doubt that the two scribes were associated with the cardinal’s establishment.

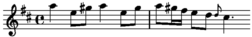

Dating almost certainly from the mid- or late 1720s, the present concerto in A major and its close contemporaries items 51 and 64 (a concerto in F major and a sinfonia in D major, respectively, available in this series as HH 023 and HH 025) are among the most mature and most innovative of Valentini’s surviving compositions. Common to all three are the absence of a viola part (a factor not uncommon in music for Ottoboni’s establishment after c.1720) and an inventive juxtaposition of wind and strings. They are further characterized by their galant expression and remarkably experimental designs: sectional movement-structures, often exhibiting, within the framework of binary form, the tendencies of incipient sonata form.7 Showing only a minimal use of solo-tutti contrast and the traditional Roman concerto grosso disposition of forces on which the composer’s earlier instrumental works had relied, this was, in its day, a new kind of ensemble music that anticipated the classical symphony.

Editorial policy and matters of performance

In this critical edition, original key signatures, time signatures and clefs are retained. For the most part, text missing from the source or otherwise added by the editor is shown within square brackets. Editorial slurs and ties are given in dashed form, except for slurs that are understood to link appoggiaturas to their main notes, which, when missing in the source, are added tacitly. (Such appoggiatura slurs are in fact entirely lacking in the manuscript for the present work.) In other cases of editorial intervention, including instances where such intervention cannot be distinguished in the main text by typographical means, the original readings are described in the Textual Notes. The original notation follows the normal convention of the early eighteenth century whereby an accidental governs only the note it precedes and any immediate repetitions of that note, whether barlines intervene or not. The conversion to modern notation has thus entailed the tacit suppression of accidentals that are redundant in today’s usage (where an inflexion,

occurring earlier in the bar has not been cancelled) and the tacit addition of others (after a barline, when an inflected pitch continues to apply). An accidental omitted from the source in error is recorded in the Textual Notes if an accidental occurring earlier in the bar remains valid, by modern convention, for the pitch in question; it is otherwise restored in square brackets in the normal way. Editorial cautionary accidentals are given within round brackets; cautionary accidentals included in the source are reproduced without brackets.

As was mentioned earlier, the bass in movements i, ii and iv is surely intended to be realized, even though the source provides no figures for the continuo part. An entirely unfigured, or only sparsely figured, bass is not in itself unusual; professional musicians of Valentini’s day were typically expected to realize basso continuo extempore, without the aid of figures – especially in the case of Italian music such as this in which the harmonic progression is mostly straightforward. Naturally, the editorial figures included in the present edition do not provide the only possible harmonic solution in every instance; their purpose is to ensure that a complete text is presented and to assist continuo players inexperienced in realizing unfigured basses. (A version of this score with a written-out continuo realization is available separately.) The size and complexion of the continuo group (which may of course include, besides cello and harpsichord, a double bass playing at sixteen-foot pitch and an archlute or theorbo) is best determined in relation to the number of players allotted to the violin parts. Concertos such as this were typically intended for fairly small forces. Although an interpretation with one player per part is in some cases the most appropriate choice, performances of the present work that employ at least two or three players on each string part are more likely to realize the powerful vigour of this music. Such doubling is in any case implicit in the fact that the present manuscript provides pairs of virtually identical parts for first violin, second violin and basso. The wind parts, naturally, are not meant to be doubled – but neither are they to be regarded as ‘solo’ instruments to be accompanied.

The source is quite specific with regard to dynamics, trills, appoggiaturas, slurring and staccato, presumably in reflection of the composer’s own wishes. Accordingly, editorial markings concerning interpretation are added mostly by analogy with original ones. In works such as this, forte (intended to mean a ‘normal’, full-bodied sonority) is typically assumed rather than explicitly marked, especially at the beginning of a fast movement and for ritornellos. Accordingly, piano means a relative reduction from that norm, not soft in an absolute sense; only pianissimo, when specified, requires a particularly hushed sound. Further dynamic variation may, of course, be applied from

moment to moment. Even so, the ideal communication of the music of Valentini’s time

depends far less on dynamic contrast than on subtle variations in tempo, articulation and embellishment. The cello solo featured in the third movment may be appropriately graced by the player, and here, too, one finds at bars 18,

31 and 37 opportunities for insertion of short

cadenzas if desired.

Paul Everett

Cork, March 2001

1 For detailed information on Valentini’s life and works, see Michael Talbot, ‘A Rival of Corelli: the Violinist-Composer Giuseppe Valentini’, in Sergio Durante & Pierluigi Petrobelli (eds), Nuovissimi studi corelliani (Olschki, Florence, 1982), pp. 347–65; and Enrico Careri, ‘Giuseppe Valentini (1681–1753): Documenti inediti’, Note d’Archivio, 5 (1987), pp. 69–125.

2 See Enrico Careri, Catalogo dei manoscritti musicali dell’Archivio Generale delle Scuole Pie a San Pantaleo (Torre d’Orfeo, Rome, 1987). Incipits and other details of the manuscripts (five concertos and one sinfonia) in the Saxon State Library, Dresden, are given in Paola Pozzi, ‘Il concerto strumentale italiano alla corte di Dresda durante la prima metŕ del settecento’, in Albert Dunning (ed.), Intorno a Locatelli. Studi in occasione del tricentenario della nascitŕ di Pietro Antonio Locatelli (1695–1764) (Libreria Musicale Italiana, Lucca, 1995), pp. 953–1037: 1027–9.

3 The most recent evaluation of evidence linking Valentini with Ottoboni’s court is Stefano La Via, ‘Il Cardinale Ottoboni e la musica: nuovi documenti (1700–1740), nuove letture e ipotesi’, in Dunning, Intorno a Locatelli, cit., pp. 319–526; especially pp. 340, 361–3 and 499.

4 Thirteen volumes exist in the Central Library, Manchester, shelfmark MS 580 Ct 51. A further partbook which completes the set, referred to below and in former literature as volume xiv, survives in the British Library, London, shelfmark RM.22.c.28. We are grateful to Manchester Public Libraries and the British

Library for permission to use this source for the present edition.

5 See Paul Everett, The Manchester Concerto Partbooks (Garland, New York & London, 1989).

6 See Paul Everett, ‘A Roman Concerto Repertory: Ottoboni’s “what not”?’, Proceedings of the Royal Musical

Association, 110 (1983–84), pp. 62–78.

7 The technical features of these works are explored in Everett, Manchester Concerto Partbooks, cit., pp. 325–42.

|